Our guest speaker Sheila Antrobus set the scene by describing the enormous differences between the population during Queen Victoria’s reign. The Queen and her consort, Prince Albert had nine children during their marriage, five girls and four boys. All of these children would have been brought up mainly by ‘wet nurses’ and other servants, educated by individual tutors and somewhat ignored by their parents while young. They would have had the best of everything during their childhood.

We then saw, and heard about, the stark contrast between the Royal Family and the Upper Classes to the lives of the ‘working class’. There were no ‘middle class’ of people for most, if not all, of Victoria’s reign.

Sheila's first image relating to the working class was of a yard, with houses around it. She pointed out a channel running through the centre of the yard, which would have been an open sewer taking waste away from the dwellings, and the constant stench, especially on warm days, which would be suffered by the residents. Many of the people living there would have one room for their family, as well as having to share rooms with others. While upper class children received private education, their counterparts started employment early – at ten years or even younger. Boys would, for example, collect faeces left by cats and dogs to sell to factories who processed and softened leather. The girls might make posies and then sell them on the street or find employment in rope making. Despite their ages, children would have to work long hours, as did their parents.

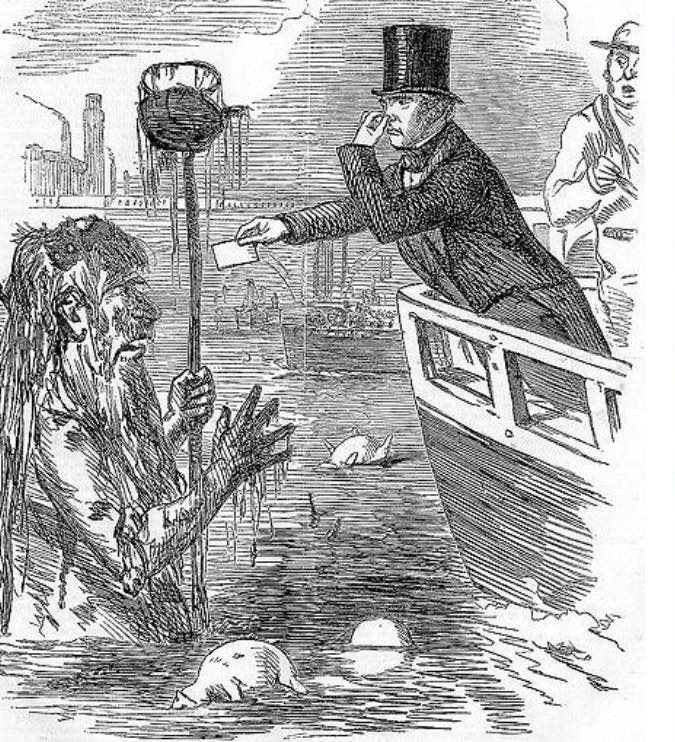

Alongside these disparities between the population, the Industrial Revolution was taking place. This brought about many new inventions and innovation. Steel ships were being constructed, the railway system was developed, and more factories began to turn out goods sent around the world. Other means of transport replaced the thousands of horses, and what they left behind. The manure contributed to an event known as ‘The Great Stink’ of 1858 and played a part in prompting the invention and building of the water and sewage systems of London by Joseph Bazalgette. Consequently, a piece of jewellery known as a Vinegarette was invented. This was a small silver case, which contained a piece of cloth infused with perfume or similar, as some relief from the ‘stink’.

Prince Albert, who was not popular with the majority of the Queen’s subjects, organised the Great Exhibition in 1837, which was a great success in advertising and informing people from across the world about Britain’s achievements. With over one hundred thousand exhibits, the exhibition attracted over six million visitors in the first six months.

Sheila began to tell us about the antique jewellery and other items that the Victorians, the wealthy ones at least, would have had or been familiar with. First mentioned were sovereigns, which one of her clients thought were a set of twelve farthings. The coins were sovereigns, roughly the same dimensions of farthings; but made of 22 carat gold. We saw images of the three designs of sovereigns which featured the queen. These are the ‘young head’ of the monarch, one with Victoria with a veiled head, and one dating from 1893 to 1901 known as the ‘old head’.

Prince Albert designed, and made, many items of jewellery for his wife but her favourite was a single brass locket which contained locks of her father’s, and Albert’s hair. The Victorians were obsessed with jewellery, including jewellery from the sea. We saw images of a red cameo – which means carved - brooch, necklace and bracelet; the red stone perhaps purchased on the ‘Grand Tour’ of Europe in the eighteenth century. Such items are still available today: they are for sale, on the ‘Ponte Vecchio’ in Florence, known already to some of our members.

We also saw jewellery from the land – butterscotch, and amber coloured beads, Sheila spotting some amber examples worn by a member of her audience today. She showed us a Chatelaine belt, worn around the waist. Attached to the belt were items that were used by ladies of the time, or their housekeepers. These included scissors, an aide memoire, a thimble case and other items. Chatelaines are more likely nowadays to be seen mainly in museums.

Moving on to the jewellery gentlemen of these times would have, Sheila started with pocket watches, the first one without a cover. One with a lid made of half gold and half glass was a ‘Half Hunter’, and one without any glass in its cover is known as a ‘Full Hunter’. The carat of gold showed how wealthy the wearer was, from 22 carat to 14 carat – other watches were available too. The actual value of these watches, however, is the quality of the mechanism or ‘workings’ of the timepiece. The chain which connects the watch to its wearer is called the ’Albert’ chain – we could have guessed who it was named after by now.

Another symbol of wealth for the man would have been a walking cane. This usually wasn’t a sign of any difficulty in walking, which was very popular during Queen Victoria’s reign. We saw a handle of one of these canes; made of ivory and carved into an image of a snake – a symbol of everlasting love.

After the death of Prince Albert in December 1861, Queen Victoria displayed such an emotion for many years, perhaps until she passed away. She mourned for at least 12 months, refused to carry out any duties for some time, and wore black clothes for the next forty years. After 1861 mourning jewellery began to be made and sold, again much of it was black, containing Jet either from Britain or France.

But when Queen Victoria died in 1901, she was buried wearing a white dress. On her right side, she had Prince Albert’s dressing gown, and a plaster cast of his right hand. On her left side, underneath a posy, she had a photo of John Brown and a lock of his hair in her hand. She also had rings on every finger, and gold chains around her neck.

As well as showing us many images of jewellery and clothing worn during Victoria’s life, Sheila had much to tell us about the Victorians – many of whom are still well known. The queen met many famous, and diverse, people during her reign such as ‘General Tom Thumb, who actually had a wife and family, PT Barnum, ‘Buffalo Bill’ Cody and Joseph Merrick, the ‘Elephant Man’.

We were reminded of who and what became famous during the Victorian era, such as Thomas Cook, William Morris, Gilbert and Sullivan and Oscar Wilde. It was also the age of the Music Hall, dance cards and calling cards. This was alongside the abolition of slavery, creation of canal routes, and numerous inventions either still being used or adapted over the years.